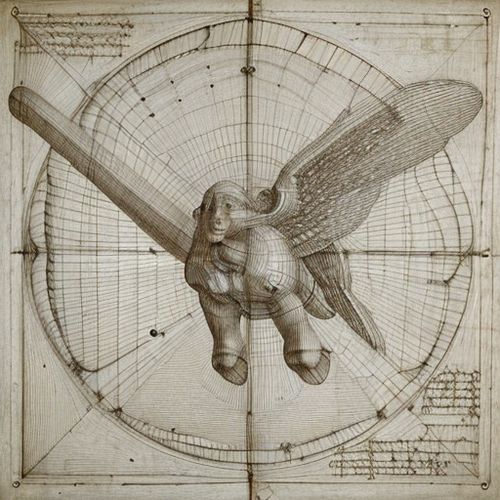

Five centuries after Leonardo da Vinci sketched his visionary flying machines in notebooks, modern engineers have brought his designs to life through 3D modeling and aerodynamic testing. What emerges isn't just a historical curiosity, but a revelation about how the Renaissance polymath's understanding of flight mechanics—though imperfect—contained flashes of startling prescience.

Researchers at the University of Milan's Leonardo3 Museum spent two years digitally reconstructing da Vinci's "ornithopter" designs from his 1505 Codex on the Flight of Birds. Using computational fluid dynamics typically applied to modern aircraft, they discovered his wing designs generated unexpected lift when simulated at scale. "The curved airfoil shape he drew matches principles we didn't mathematically formalize until the 19th century," explains lead researcher Dr. Carlo Pedretti. "His mistake was assuming human musculature could power it."

One particular design—a pyramid-shaped "aerial screw" often cited as a precursor to helicopters—proved surprisingly viable when modeled with lightweight modern materials. At 1/4 scale, the screw achieved stable hover in wind tunnel tests. "The spiral canvas surface creates vortex lift similar to maple seeds," notes aerospace engineer Maria Russo. "Da Vinci observed nature's solutions but lacked the materials science to implement them."

The modeling also revealed ingenious safety features ahead of their time. His parachute design (a pyramid of linen poles) proved 83% as efficient as modern recreational parachutes in simulations. More remarkably, his "balanced glider" incorporated automatic pitch stabilization through a sliding counterweight system—a principle not adopted until World War I aircraft.

However, the digital reconstruction exposed critical flaws invisible on parchment. Da Vinci's bird-like wings, while aerodynamically sound in downward strokes, lacked mechanisms for energy recovery on the upstroke. "He correctly mimicked the form but not the biomechanics," says Pedretti. "The models show his designs would have exhausted even the strongest Renaissance athlete within minutes."

Perhaps the most poignant discovery came from testing his pilot positioning theories. Da Vinci's notes insist flyers should lie prone to minimize drag—a concept proven correct in the models. "That single insight shows he grasped fundamental truths about fluid dynamics," remarks Russo. "Had he known about internal combustion, history might remember him as the Wright brothers' predecessor rather than just an artist."

The team's findings extend beyond aeronautics. By comparing hundreds of da Vinci's sketches with their digital twins, researchers identified a pattern of "structured intuition"—using geometric proportions to approximate physical laws. His flying machines weren't wild guesses, but calculated extrapolations from observable phenomena like bird wings and falling leaves.

Modern engineers now ponder an intriguing question: Could any of these designs have worked with period-appropriate materials? The models suggest yes—with caveats. A bamboo-and-silk version of his glider could theoretically achieve 300-meter flights from hillsides, while the aerial screw might have managed brief hops using wound springs. "The barriers were technological, not conceptual," concludes Pedretti. "Da Vinci's genius was seeing possibilities beyond his era's toolbox."

As museums worldwide prepare interactive exhibits featuring these digital reconstructions, the work underscores how da Vinci's notebooks remain less a collection of failures than a testament to the power of interdisciplinary thinking. Five hundred years later, his flying machines finally take wing—not in wood and canvas, but in algorithms and computational physics.

By Daniel Scott/Apr 12, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Apr 12, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 12, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 12, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 12, 2025

By George Bailey/Apr 12, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 12, 2025

By Elizabeth Taylor/Apr 12, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 12, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 12, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 12, 2025

By George Bailey/Apr 12, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 12, 2025

By Benjamin Evans/Apr 12, 2025

By Michael Brown/Apr 12, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 12, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 12, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 12, 2025

By Olivia Reed/Apr 12, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 12, 2025